Note: It was announced in November 2023 that MoneyOwl will be acquired by Temasek Trust to serve communities under a re-purposed model, and will move away from direct sale of financial products. The article is retained with original information relevant as at the date of the article only, and any mention of products or promotions is retained for reference purposes only.

______________

The latest thing that has pounded already-stressed global markets is the UK (pun intended). The new British PM and Chancellor’s trickle-down economics budget of income and property tax cuts benefitting the wealthy, with a lifting of a cap on banker bonuses thrown in, was not only a political bombshell. It drove the sterling pound to record lows against the USD and triggered a sell-off in gilts (UK government bonds), on worries that already-high inflation would go up more as the government needs to borrow more to fund spending to make up for lost tax revenue. It brought back memories of the UK sterling crisis in the mid-1970s when this major economy went cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout. This time round, the IMF delivered a rebuke to the UK: rare for developed countries. Global equity markets were driven down, and the US Dollar strengthened, as did US Treasuries. There was some reprieve after the Bank of England announced that it would buy long-dated gilts to stabilise the gilt market, once again doing Quantitative Easing, a reversal of their earlier plan to start Quantitative Tightening this year. But it was short-lived, though the sterling has stayed above its lows as at the time of writing.

On one hand, it appears that the Bank of England was being forced to finance government spending by printing money. But it has explained that it was trying to prevent a meltdown in gilt market because UK pension funds were selling off gilts, in a spiral that would have risked insolvency at the pension funds. The mechanics are complicated, but it appears that fund managers of UK pension funds, who need to avoid accounting losses due to marketing up of liabilities that occur when yields decrease, had chalked up GBP 1.5 trillion worth of derivatives like interest rate swaps to hedge such liability mismatches. When investors started to sell gilts after the UK budget announcement, forcing yields up pension fund managers were forced to post cash collateral in response to margin calls. They then had to sell down their holdings of gilts for cash, driving gilt prices further down in a dangerous spiral, a near-Lehman moment which the Bank of England stepped in to stop.[1]

Once again, leverage, financial engineering and accounting rules affecting fund manager careers, have turned what should have been the ultimate “buy and hold” long-term investments of pension funds, into financial bombshells. As I often say to clients, who are mainly everyday Singaporeans, you are not a fund manager and you do not have to live a fund manager’s life and make trade-offs with your client’s long-term interests because of your job pressures using fancy structures or solutions, and end up only benefitting bankers’ (now uncapped) bonuses. The beautiful thing about the family offices of all of us ordinary folk, as opposed to billionaires, is that they are not managed by fund managers who need to show that they are doing something and outperforming other professionals in the short-term to avoid getting fired.

Instead, you can, and should, use advisers who choose fund managers who do not engage in such activity, like shifting your asset allocations because of short-term data or because they are compelled to demonstrate they can pick companies to outperform in each macroeconomic situation all the time. There aren’t that many of such fund managers who make the cut, which is why at MoneyOwl we have admitted only a few rather than hundreds of funds. We curate rather than proliferate and emphasise quality, not variety. This is not to say that there aren’t strong headwinds facing the global economy in the next few months or even the next one or two years. The crisis is one of credibility, specifically, the ability of governments and central banks of major economies to rein in inflation and at the same time avoid a hard recession. To be fair, there have been multiple shocks over the last several years: the Covid-19 pandemic, leading to a huge government and monetary stimulus, supply-side shocks and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, pressurising food and energy prices. Policymakers have their work cut out for them.

The other major concern is that of US dollar strength. Whatever your views on the US economy may be, the dominance of the US dollar and US capital markets far outweighs its economy’s relative size: it represents more than 80% of world foreign exchange transactions, 60% of official foreign reserves, and half of cross-border loans and trade invoices. [2] As a result, the US dollar is still the dominant place where investors take refuge in stressed times, but the risk is that the financial outflows from the rest of the world into the US cause weaker currencies elsewhere, especially in places where foreign reserves are low and spending is high. Countries would then have to also raise interest rates or tighten the monetary supply to support their currencies, and this causes a contractionary impact on domestic economies. US dollar strength is currently buttressed by the Federal Reserve’s determination to quash domestic inflation by raising rates – and the US is not about to change its domestic policy because the rest of the world suffers. Individually, each country will also try to dampen inflation, especially wage-price spirals; at home in Singapore, the government has already recently signalled its concern about this, meaning that wages cannot increase ahead of productivity.

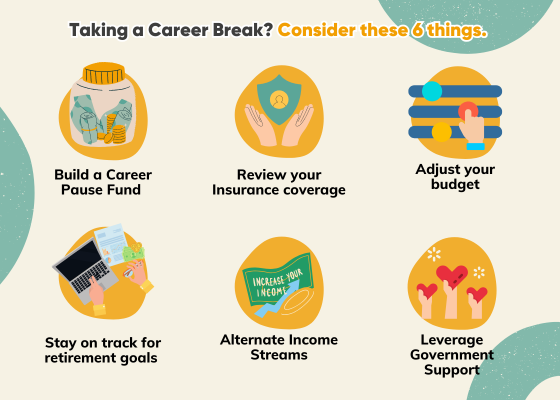

In our personal lives, geopolitical problems, economic downturns and inflation will be uncomfortable and require some intentional re-budgeting and belt-tightening. Our short-term money equation is the foundation of comprehensive financial planning. As long-term investors, however, we should look to opportunities as markets re-price. The markets have good deals even for those just looking to earn cash rates for their rainy day funds at low to no risk. As the saying goes, when the tide goes out, you find out who has been swimming naked. When bonds are stressed, this is when you tell which “cash management account” is true cash, and which were actually made up of bonds with credit risks. Take a read here.

Yes, it is true that economic headwinds can translate into market downturns and vice versa. When companies’ earnings outlooks are poor, investors may sell down their stock. Venture capital-funded start-ups are facing a winter and may run out of cash. But for the diversified investor who hasn’t been chasing just one sector’s stocks or trying to time the markets, you can look beyond the news of the day to the long-term potential of the market. Even in past periods of the much-feared stagflation, US broad equity markets have delivered positive real returns in nine out of 12 stagflation years, and bonds, in five out of the same.

So the age-old wisdom applies. The economy is not the market. Stick to your financial plan, have an emergency fund (and be cheered by better rates without sacrificing safety), and for your excess cash, stay invested in public markets, which is the best safeguard for your long-term goals and your best bet of beating inflation over the long term. Don’t be too greedy about catching the bottom because you won’t know when that would be, it is often ahead of the economy and soon after investors’ worst sentiments. Instead, keep dollar-cost averaging into your nest egg, by buying tranches at discount from the peak at regular intervals. You will reap your gains when the recovery comes, and this upturn can be fast and furious. It is often in such times like this when the seeds for big returns are sown for a bumper harvest in the future.

[1] For an excellent exposition of this, read Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine’s “Money Stuff: UK Pensions Got Margin Calls” at https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-09-29/uk-pensions-got-margin-calls#xj4y7vzkg

[2] Source: Martin Wolf, “Why the strength of the dollar matters”, Financial Times, 27 Sep 2022

Disclaimer:

While every reasonable care is taken to ensure the accuracy of information provided, no responsibility can be accepted for any loss or inconvenience caused by any error or omission. The information and opinions expressed herein are made in good faith and are based on sources believed to be reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. Expressions of opinions or estimates should neither be relied upon nor used in any way as indication of the future performance of any financial products, as prices of assets and currencies may go down as well as up and past performance should not be taken as indication of future performance. The author and publisher shall have no liability for any loss or expense whatsoever relating to investment decisions made by the reader.